Employee Equity: Dilution

Last week I kicked off my MBA Mondays series on Employee Equity. Today I am going to talk about one of the most important things you need to understand about employee equity; it is likely to be diluted over time.

When you start a company, you and your founders own 100% of the company. That is usually in the form of founders stock. If you never raise any outside capital and you never give any stock away to employees or others, then you can keep all of that equity for yourself. It happens a lot in small businesses. But in high growth tech companies like the kind I work with, it is very rare to see the founders keep 100% of the business.

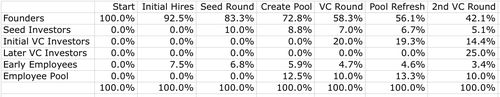

The typical dilution path for founders and other holders of employee equity goes like this:

1) Founders start company and own 100% of the business in founders stock

2) Founders issue 5-10% of the company to the early employees they hire. This can be done in options but is often done in the form of restricted stock. Sometimes they even use "founders stock" for these hires. Let's use 7.5% for our rolling dilution calculation. At this point the founders own 92.5% of the company and the employees own 7.5%.

3) A seed/angel round is done. These early investors acquire 5-20% of the business in return for supplying seed capital. Let' use 10% for our rolling dilution calcuation. Now the founders own 83.25% of the company (92.5% times 90%), the employees own 6.75% (7.5% times 90%), and the investors own 10%.

4) A venture round is done. The VCs negotiate for 20% of the company and require an option pool of 10% after the investment be established and put into the "pre money valuation". That means the dilution from the option pool is taken before the VC investment. There are two diluting events going on here. Let's walk through them both.

When the 10% option pool is set up, everyone is diluted 12.5% because the option pool has to be 10% after the investment so it is 12.5% before the investment. So the founders now own 72.8% (83.25% times 87.5%), the seed investors own 8.75% (10% times 87.5%), and the employees now own 18.4% (6.8% times 87.5% plus 12.5%).

When the VC investment closes, everyone is diluted 20%. So the founders now own 58.3% (72.8% times 80%), the seed investors own 7% (8.75% times 80%), the VCs own 20%, and the employees own 14.7% (18.4% times 80%). Of that 14.7%, the new pool represents 10%.

5) Another venture round is done with an option pool refresh to keep the option pool at 10%. See the spreadsheet below to see how the dilution works in this round (and all previous rounds). By the time that the second VC round is done, the founders have been diluted from 100% to 42.1%, the early employees have been diluted from 7.5% to 3.4%, and the seed investors have been diluted from 10% to 5.1%.

I've uploaded this spreadsheet to google docs so all of you can look at it and play with it. If anyone finds any errors in it, please let me know and I'll fix them.

This rolling dilution calculation is just an example. If you have diluted more than that, don't get upset. Most founders end up with less than 42% after rounds of financing and employee grants. The point of this exercise is not to lock down onto some magic formula. Every company will be different. It is simply to lay out how dilution works for everyone in the cap table.

Here is the bottom line. If you are the first shareholder, you will take the most dilution. The earlier you join and invest in the company, the more you will be diluted. Dilution is a fact of life as a shareholder in a startup. Even after the company becomes profitable and there is no more financing related dilution, you will get diluted by ongoing option pool refreshes and M&A activity.

When you are issued employee equity, be prepared for dilution. It is not a bad thing. It is a normal part of the value creation exercise that a startup is. But you need to understand it and be comfortable with it. I hope this post has helped with that.