It's time for MBA Mondays again. For the third week in a row, the topic of the post has been suggested by a reader. Last week, Elia Freedman wrote:

"A suggestion for your next post. The logical follow-on is to explain the second half of the TVM (time value of money), which is compounding interest."

Before I address the issue of compounding interest, I'd like to recognize two things about the MBA Monday series. The first is that each post has a very rich comment thread attached to it. If you are seriously interested in learning this stuff, you would be well served to take the time to read the comments and the replies to them, including mine. The second is that the readers are building the curriculum for me. Each post has resulted in at least one suggestion for the next week's post. I dove into MBA Mondays without thinking through the logical progression of topics. At this point, I'm just going to run with whatever people suggest and try to assemble it on the fly. It's working well so far. So if you have a suggestion for next week's topic, or any topic, please leave a comment.

Last week, I described interest as the rate of change in the time value of money. And we broke interest rates down into the real rate, the inflation factor, and the risk factor. And we calculated that if you invested $900 today at an 11.1% rate of interest, you'd end up with $1000 a year from now.

But what happens if you wait a few years to get your money back and receive annual interest payments along the way? Let's say you invest the same $900, receive $100 each year for four years, and then in the last year, you receive $1000 (your $900 back plus the final year's $100 interest payment).

There are two scenarios here and they depend on what you do with the annual interest payments.

In the first scenario, you pocket the cash and do something else with it. In that scenario, you will realize the 11.1% rate of interest that you would have realized had you taken the $1000 one year later. It's basically the same deal, just with a longer time horizon. And your total proceeds on your $900 investment are $1400 (your $900 return of "principal" plus five $100 interest payments).

In the second scenario, you reinvest the interest payments at 11.1% each year and take a final payment in year five. If you reinvest each interest payment at 11.1% interest, at the end of year five, you will receive $1524 as your final payment. Notice that the total proceeds in this scenario are $124 higher than in the other scenario. That is because you reinvested the interest payments instead of pocketing them.

Both scenarios produce a "rate of return" of 11.1%. If you look at this google spreadsheet, you can see how these two scenarios map out. And you can see the calculation of total profit and "internal rate of return".

The fact that you make a larger profit on one versus the other at the same "rate of interest" shows the power of compounding interest. It really helps if you reinvest your interest payments instead of pocketing them. While $124 over five years doesn't seem like much, let's look at the power of compounding interest over a longer horizon.

Let's say you inherit $100,000 around the time you graduate from college. Instead of spending it on something, you decide to invest it for your retirement 45 years later. If you invest it at the 11.1% rate of interest that we've been using, the differences between pocketing the $11,100 you'd get each year and reinvesting it are HUGE.

If you pocket the $11,000 of interest each year, you will receive $599,500 on your $100,000 investment over 45 years.

But if you reinvest the $11,000 of interest each year at 11.1% interest, you will receive $11.4 million dollars when you retire. That's right. $11.4 million dollars versus $599,500. That is the power of compounding interest over a long period of time.

You can see how this models out in this google spreadsheet (sheets two and three).

Now let's tie this issue to startups and venture capital. Venture capital investments are often held for a fairly long time. I am currently serving on several boards of companies that my prior firm, Flatiron Partners, invested in during 1999 and 2000. Our hold periods for these investments are into their second decade. Of course not every venture capital investment lasts a decade or more. But the average hold period for a venture capital investment tends to be about seven or eight years.

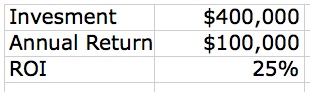

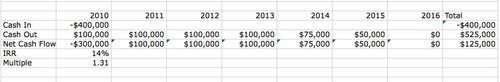

And during those seven to eight years, there are no annual interest payments. So when you calculate the rate of return on the investment, the spreadsheet looks like this. It's a compound interest situation.

If you go back to the $100,000 over 45 years example, you'll see that a return of 114x your money over 45 years produces the same "return" as 6x your money with annual interest payments.

The differences are not as great over seven or eight years but they are made greater by virtue of the fact that VCs seek to make 40-50% annual rates of return on their capital. If you read last week's post, you'll know that comes from the risk factor involved. The more risk an investment has, the higher rate of return an investor will require on their money in a successful outcome.

If you want to generate a 50% rate of return compounded over eight years on $100,000, you will need to return $2.562 million, or 25.6x your investment. See this google spreadsheet (sheet 4) for the details.

The good news is that most venture capital investments are made over time, not all at once in the first year. So the "hold periods" on the later rounds are not as long and make this math a bit easier on everyone involved (maybe a topic for next week or some other time?).

But as you can see, compounding interest over any length of time increases significantly the amount of money you need to return in order to pay the same rate of return as a security with annual interest payments. There are two big takeaways here. The first is if you are an investor, you should reinvest your interest payments instead of spending them. It makes a huge difference on the outcome of your investment. The second is if you are an entrepreneur, you should take as little money as you can at the start and always understand that your investors are seeking a return and that the time value of money compounds and makes your job as the producer of that return particularly hard.