This is a post Nick did around his User First keynote. It’s great and I wanted to feature it to the AVC community today. The comments thread at the end is also running on Nick’s blog and at usv.com so you will see commingled comments from all three places.

—————————————————–

“It is trust, more than money, that makes the world go round.”

— Joseph Stiglitz, In No One We Trust

The week before last, I visited Yahoo! to give the keynote talk at their User First conference, which brought together big companies (Google, Facebook, etc), startups (big ones like USV portfolio company CloudFlare and lots of way smaller ones), academics, and digital rights advocates (such as Rebecca MacKinnon, whose recent book Consent of the Networked is an important read) to talk about the relevance of human/digital rights issues to the management of web applications.

I was there to speak to the investor perspective — why and how we think about the idea of “user first” as we make and manage investments in this space.

First, I want to point out a few things that might not be obvious to folks who aren’t regulars in conversations about digital rights, or human rights in the context of information & communication services. First, there has been substantial work done (at the UN, among other places) to establish a set of norms at the intersection of business and human rights. Here is the UN’s guiding document on the subject. Second, in terms of digital rights, the majority of the conversation is about two issues: freedom of expression/censorship and privacy/surveillance. And third, it’s important to note that the conversation about digital rights isn’t just about the state ensuring that platforms respect user rights, but it’s equally about the platforms ensuring that the state does.

The slides are also available on Speakerdeck, but don’t make much sense without narration, so here is the annotated version:

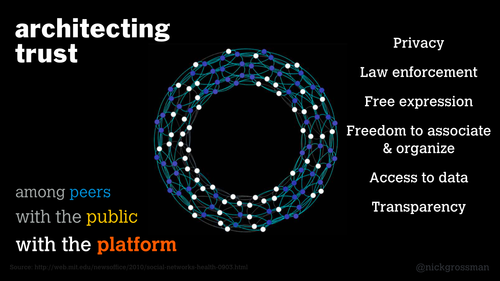

As more and more of our activities, online and in the real world, are mediated by third parties (telecom, internet and application companies in particular), they become the stewards of our speech and our information.

Increasingly, how much we trust them in that role will become a differentiating feature and a point of competition among platforms.

A little background on who I am:

I work at Union Square Ventures — we are investors in internet and mobile companies that build social applications. I also have academic affiliations at the MIT Media Lab in the Center for Civic Media, which studies how people use media and technology to engage in civic issues, and at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard Law School which studies tech & internet policy. And my background is working in the “open government” space at organizations like OpenPlans and Code for America, with a focus on open data, open standards, and open source software.

So, to start out: a guiding idea is that the internet (as we know it today) is not just an open, amorphous mass of random peer-to-peer communications. It’s actually a collection of highly architected experiences:

Whether it’s the governance structure of an open source project, the set of interactions that are possible on social platforms like Twitter and Tumblr, or the web-enabled real-world interactions that are a result of Craigslist, Airbnb, and Sidecar, much of the innovation and entrepreneurial activity in the web and mobile space has been about experimenting with architectures of collaboration.

Web & mobile technologies are giving us the opportunity to experiment with how we organize ourselves, for work, for pleasure and for community. And that in that experimentation, there are lots and lots of choices being made about the rules of engagement. (for example, the slide above comes from an MIT study that looked at which kinds of social ties — close, clustered ones, or farther, weaker ones — were most effective in changing health behavior).

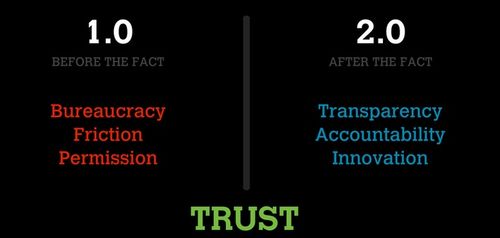

At USV, we view this as part of a broader macro shift from bureaucratic hierarchies to networks, and that the networked model of organizing is fundamentally transformative across sectors and industries.

One big opportunities, as this shift occurs, it to reveal the abundance around us.

I first heard this phrasing from Zipcar founder Robin Chase and it really stuck with me. It’s as if many of the things we’ve been searching for — whether it’s an answer to a question, an asthma inhaler in a time of emergency, a ride across town, someone to talk to, or a snowblower — are actually right there, ambient in the air around us, but it’s previously not been possible to see them or connect them.

That is changing, and this change has the potential to help us solve problems that have previously been out of reach. Which is good, because for as much progress we’ve made, there are still big problems out there to tackle:

For a (relatively) trivial one, this is what most California freeways look like every day. In much of the world, our transportation systems are inefficient and broken.

…and this is what Shanghai looked like last week as a 500-mile wide smog cloud, with 20x the established limit for toxicity, rolled in for a visit. We obviously don’t have our shit together if things like this can happen.

…and we have tons to figure out when it comes to affordable and accessible health care (not the least of which is how to build an insurance marketplace website).

…and education is getting worse and worse (for younger grades) and more and more expensive (for college). There’s no question that the supply / demand balance is out of whack, and not taking into account the abundance that is around us.

So: these are all serious issues confronting global society (and the ones I mentioned here are just a small fraction of them at that).

All of these issues can and should benefit from our newfound opportunity to re-architect our services, transactions, information flows, and relationships with one another, built around the idea that we can now surface connections, efficiencies, information, and opportunities that we simply couldn’t before we were all connected.

But… in order to do that, the first thing we need to do is architect a system of trust — one that nurtures community, ensures safety, and takes into account balances between various risks, opportunities, rights and responsibilities.

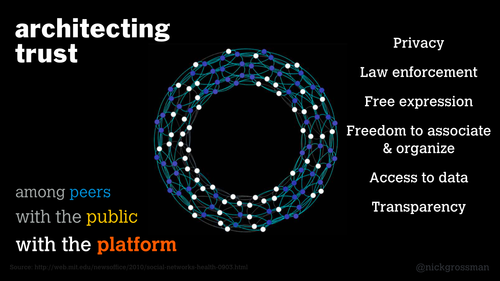

Initially, that meant figuring out how to get “peers” in the network to trust each other — the classic example being Ebay’s buyer and seller ratings which pioneered the idea of peer-to-peer commerce. Before then, the idea of transacting (using real money!) with a stranger on the internet seemed preposterous.

Recently, the conversation has shifted to building trust with the public, especially in the context of regulation, as peer-to-peer services intersect more and more with the real world (for example, Airbnb, Uber, and the peer-to-peer ride sharing companies and their associated regulatory challenges over the past three years).

Now, a third dimension is emerging: trust with the platform. As more and more of our activities move onto web and mobile platforms, and these platforms take on increasing governance and stewardship roles, we need to trust that they are doing it in good faith and backed by fair policies. That trust is essential to success.

In terms of network & community governance, platforms establish policies that take into account issues like privacy, enforcement of rules (both public laws and network-level policies), freedom of expression and the freedom to associate & organize, and transparency & access to data (both regarding the policies and activities of the platform, and re: the data you produce as a participant in the community).

When you think about it, you realize that these are very much the same issues that governments grapple with in developing public policy, and that web platforms actually look a lot like governments.

Which makes sense, because both in the case of governments and web-enabled networks, the central task is to build an architecture around which other activity happens. You build the roads and the other essential public infrastructure, and then you set the ground rules which enable the community and economy to function.

Of course, there is a major difference: web networks are not governments, and are not bound by all the requirements & responsibilities of public institutions. They are free to create their own rules of engagement, which you agree to when you decide to participate (or not) in that community.

This is both a plus and a minus, when it comes to user rights — the major plus being that web platforms are competitive with each other. So that when there are substantive differences in the way platforms make and enforce rules, those differences can be the basis for user choice (e.g., it’s easier to move from Facebook to Google than it is to move from the US to Canada).

I would like to put some extra emphasis on the issue of data, since it’s growing so quickly and has been so much at the forefront of the public conversation over the past year.

We are generating — and sharing — more data than we ever have before.

Everywhere we go, on the internet and in the real world, we are leaving a trail of breadcrumbs that can mined for lots of purposes. For our own good (e.g., restaurant recommendations, personal health insights), for social purposes (crowdsourced traffic reports, donating data to cancer research), for commercial purposes (ad targeting & retargeting, financing free content), and for nefarious purposes (spying, identity theft).

One distinguishing idea within all of this is the difference between data sharing that we opt into and data sharing that happens to us. Certain web services (for example USV portfolio company Foursquare, highlighted above) make a business out of giving people a reason to share their data; getting them to buy into the idea that there’s a trade going on here — my data now for something of value (to me, to my friends, to the world) later. It’s proving true that lots of people will gladly make that trade, given an understanding of what’s happening and what the benefits (and risks) are.

Convincing someone to share their data with you (and with others on your platform) is an exercise in establishing trust.

And my feeling is that the companies that best establish that trust, and best demonstrate that they can stand behind it, are going to be the ultimate winners.

I think about this a lot in the context of health. There is so much to gain by sharing and collecting our health data.

And If we don’t get this right (“this” being the sensitive matter of handling personal data), we miss out on the opportunity to do really important things.

And there is no shortage of startups working to: a) help you extract this data (see 23andme), b) help you share this data (see Consent to Research and John Wilbanks’ excellent TED talk on sharing our health data), and c) building tools on top of this data (see NYU Med Center’s virtual microscope project).

We are pushing the boundaries of what data people are willing to share, and testing the waters of who they’re willing to share it with.

Which brings us back to the idea of competition, and why winning on trust is the future.

We are just just just scratching the surface of understanding whether and how to trust the applications we work with.

EFF’s Who Has Your Back report ranks major tech & communications firms on their user protection policies. The aptly-titled Terms of Service; Didn’t Read breaks down tech company Terms of Service and grades them using a crowdsourced process. And, most effectively (for me at least), the Google Play store lists the data access requests for each new application you install (“you need my location, and you’re a flashlight??”).

You might be saying: “that’s nice, but most people don’t pay any attention to this stuff”.

That may be true now, but I expect it to change, as we deal with more and more sensitive data in more parts of our lives, and as more companies and institutions betray the trust they’ve established with their users.

There is no shortage of #fail here, but we can suffice for now with two recent examples:

Instagram’s 2012 TOS update snafu caught users by surprise (who owns my photographs?), and this summer’s NSA surveillance revelations have caused a major dent in US tech firms’ credibility, both at home and especially abroad (not to mention what it’s done to the credibility of the US gov’t itself).

So… how can web and mobile companies win on trust?

We’re starting to see some early indications:

Notice the major spike in traffic for the privacy-oriented search engine, USV portfolio company, DuckDuckGo, around June of 2013, marked by [I] on the graph.

Some companies, like Tumblr, are experimenting with bringing more transparency to their policy document and terms of service. Tumblr’s TOS include “plain english” summaries, and all changes are tracked on Github.

And of course, lots of tech companies are beginning to publish transparency reports — at the very least, starting to shine some light on the extent to which, and the manner in which, they comply with government-issued requests for user data. Here are Google’s, Yahoo’s and Twitter’s.

There are juicier stories of platforms going to bat for their users, most recently Twitter fighting the Manhattan DA in court to protect an Occupy protester’s data (a fight they ultimately lost), and secure email provider Lavabit shutting down altogether rather than hand over user data to US authorities in the context of the Snowden investigation.

And this will no doubt continue be a common theme, as web and mobile companies to more and more for more of us.

And, I should note — none of this is to say that web and mobile companies shouldn’t comply with lawful data requests from government; they should, and they do. But they also need to realize that it’s not always clear-cut, that they have an opportunity (and in many cases a responsibility) to think about the user rights implications of their policies and their procedures when dealing with these kinds of situations.

Finally: this is a huge issue for startups.

I recently heard security researcher Morgan Marquis-Boire remark that “any web startup with user traction has a chance of receiving a government data request approaching 1”. But that’s not what startups are thinking about when they are shipping their first product and going after their first users. They’re worried about product market fit, not what community management policies they’ll have, how they’ll respond when law enforcement comes knocking, or how they’ll manage their terms of service as they grow.

But, assuming they do get traction and the users come, these questions of governance and trust will become central to their success.

(side note: comments on this post are combined with this post on nickgrossman.is and this thread on usv.com, as an experiment)