Today on MBA Mondays we are going to talk about one of the most important things in business, the profit and loss statement (also known as the P&L).

Picking up from the accounting post last week, there are two kinds of accounting entries; those that describe money coming into and out of your business, and money that is contained in your business. The P&L deals with the first category.

A profit and loss statement is a report of the changes in the income and expense accounts over a set period of time. The most common periods of time are months, quarters, and years, although you can produce a P&L report for any period.

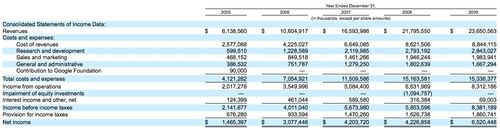

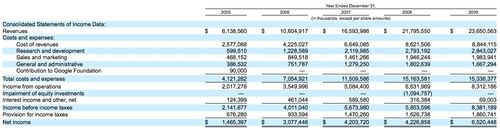

Here is a profit and loss statement for the past four years for Google. I got it from their annual report (10k). I know it is too small on this page to read, but if you click on the image, it will load much larger in a new tab.

The top line of profit and loss statements is revenue (that's why you'll often hear revenue referred to as "the top line"). Revenue is the total amount of money you've earned coming into your business over a set period of time. It is NOT the total amount of cash coming into your business. Cash can come into your business for a variety of reasons, like financings, advance payments for services to be rendered in the future, payments of invoices sent months ago.

There is a very important, but highly technical, concept called revenue recognition. Revenue recognition determines how much revenue you will put on your accounting statements in a specific time period. For a startup company, revenue recognition is not normally difficult. If you sell something, your revenue is the price at which you sold the item and it is recognized in the period in which the item was sold. If you sell advertising, revenue is the price at which you sold the advertising and it is recognized in the period in which the advertising actually ran on your media property. If you provide a subscription service, your revenue in any period will be the amount of the subscription that was provided in that period.

This leads to another important concept called "accrual accounting." When many people start keeping books, they simply record cash received for services rendered as revenue. And they record the bills they pay as expenses. This is called "cash accounting" and is the way most of us keep our personal books and records. But a business is not supposed to keep books this way. It is supposed to use the concept of accrual accounting.

Let's say you hire a contract developer to build your iPhone app. And your deal with him is you'll pay him $30,000 to deliver it to you. And let's say it takes him three months to build it. At the end of the three months you pay him the $30,000. In cash accounting, in month three you would record an expense of $30,000. But in accrual accounting, each month you'd record an expense of $10,000 and because you aren't actually paying the developer the cash yet, you charge the $10,000 each month to a balance sheet account called Accrued Expenses. Then when you pay the bill, you don't touch the P&L, its simply a balance sheet entry that reduces Cash and reduces Accrued Expenses by $30,000.

The point of accrual accounting is to perfectly match the revenues and expenses to the time period in which they actually happen, not when the payments are made or received.

With that in mind, let's look at the second part of the P&L, the expense section. In the Google P&L above, expenses are broken out into several categories; cost of revenues, R&D, sales and marketing, and general and administration. You'll note that in 2005, there was also a contribution to the Google Foundation, but that only happened once, in 2005.

The presentation Google uses is quite common. One difference you will often see is the cost of revenues applied directly against the revenues and a calculation of a net amount of revenues minus cost of revenues, which is called gross margin. I prefer that gross margin be broken out as it is a really important number. Some businesses have very high costs of revenue and very low gross margins. And example would be a retailer, particularly a low price retailer. The gross margins of a discount retailer could be as low as 25%.

Google's gross margin in 2009 was roughly $14.9bn (revenue of $23.7bn minus cost of revenues of $8.8bn). The way gross margin is most often shown is as a percent of revenues so in 2009 Google's gross margin was 63% (14.9bn divided by 23.7). I prefer to invest in high gross margin businesses because they have a lot of money left after making a sale to pay for the other costs of the business, thereby providing resources to grow the business without needing more financing. It is also much easier to get a high gross margin business profitable.

The other reason to break out "cost of revenues" is that it will most likely increase with revenues whereas the other expenses may not. The non cost of revenues expenses are sometimes referred to as "overhead". They are the costs of operating the business even if you have no revenue. They are also sometimes referred to as the "fixed costs" of the business. But in a startup, they are hardly fixed. These expenses, in Google's categorization scheme, are R&D, sales and marketing, and general/admin. In layman's terms, they are the costs of making the product, the costs of selling the product, and the cost of running the business.

The most interesting line in the P&L to me is the next one, "Income From Operations" also known as "Operating Income." Income From Operations is equal to revenue minus expenses. If "Income From Operations" is a positive number, then your base business is profitable. If it is a negative number, you are losing money. This is a critical number because if you are making money, you can grow your business without needing help from anyone else. Your business is sustainable. If you are not making money, you will need to finance your business in some way to keep it going. Your business is unsustainable on its own.

The line items after "Income From Operations" are the additional expenses that aren't directly related to your core business. They include interest income (from your cash balances), interest expense (from any debt the business has), and taxes owed (federal, state, local, and possibly international). These expenses are important because they are real costs of the business. But I don't pay as much attention to them because interest income and expense can be changed by making changes to the balance sheet and taxes are generally only paid when a business is profitable. When you deduct the interest and taxes from Income From Operations, you get to the final number on the P&L, called Net Income.

I started this post off by saying that the P&L is "one of the most important things in business." I am serious about that. Every business needs to look at its P&L regularly and I am a big fan of sharing the P&L with the entire company. It is a simple snapshot of the health of a business.

I like to look at a "trended P&L" most of all. The Google P&L that I showed above is a "trended P&L" in that it shows the trends in revenues, expenses, and profits over five years. For startup companies, I prefer to look at a trended P&L of monthly statements, usually over a twelve month period. That presentation shows how revenues are increasing (hopefully) and how expenses are increasing (hopefully less than revenues). The trended monthly P&L is a great way to look at a business and see what is going on financially.

I'll end this post with a nod to everyone who commented last week that numbers don't tell you everything about a business. That is very true. A P&L can only tell you so much about a business. It won't tell you if the product is good and getting better. It won't tell you how the morale of the company is. It won't tell you if the management team is executing well. And it won't tell you if the company has the right long term strategy. Actually it will tell you all of that but after it is too late to do anything about it. So as important as the P&L is, it is only one data point you can use in analyzing a business. It's a good place to start. But you have to get beyond the numbers if you really want to know what is going on.

Yochai Benkler is one of a handful of people who our firm regards as inspirators. We've read everything he's written and find ourselves quoting him regularly in meetings. This is a picture of Yochai making a point at our first Union Square Sessions event on peer production.

Yochai Benkler is one of a handful of people who our firm regards as inspirators. We've read everything he's written and find ourselves quoting him regularly in meetings. This is a picture of Yochai making a point at our first Union Square Sessions event on peer production.