When Talking About Business Models, Remember That Profits Equal Revenues Minus Costs

There is no shortage of discussion about Internet business models these days. And they almost always focus on revenues. But revenues are only half of the value creation equation. The other half is costs.

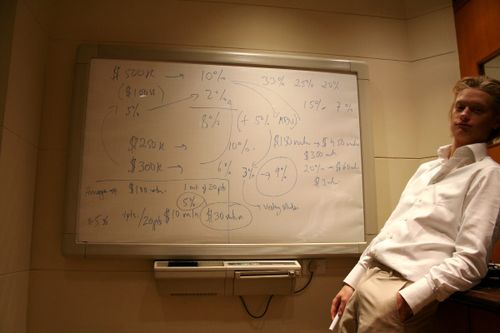

Let me explain. Businesses are worth the net present value of future cash flows. Cash flows means profits basically (capital expenditures are important but I'm going to leave them out of the discussion on this post). So a business is worth the sum of all of its future profits, discounted back to a net present value. For those who don't want a lesson in finance, you can simplify this theory even more by using a cash flow multiple as a proxy for a net present value. I like to use a 10x multiple for cash flow as a simplistic proxy for net present value.

So with that simplification, the value of a business is approximated by 10 x (revenues – costs). You can focus on creating value by driving revenues or you can focus on creating value by driving profits. And they are not the same. Because costs don't have to grow linearly with revenues.

Chris Anderson wrote a very good piece in today's WSJ called The Economics Of Giving It Away. In that essay, Chris wrote:

Meanwhile YouTube is still struggling to match its popularity with

revenues and Facebook is selling commodity ads for pennies after its

effort to charge for intrusive advertising led to a user backlash. And

news-sharing site Digg, for all its millions of users, still doesn't

make a dime. A year ago, that hardly mattered: The business model was

"build to a lucrative exit, preferably in cash." But now the exit doors

are closed and cash flow is king.

Chris goes on to suggest that Internet entrepreneurs are going to have to get people to step up and pay for something instead of just giving everything away for free because advertising isn't going to foot the bill for every company. That may well be true and we are certainly thinking that way for most, if not all, of our portfolio companies. But Chris's examples, particularly Facebook and Digg, are examples of companies that might benefit from looking at the cost side of the profit equation at some point (maybe not yet).

Let's look at Craiglist. I've heard people estimate that they are doing close to $100mm in annual revenues at this point. Many say, "they could be doing so much more". But the Craigslist profit equation is interesting. They apparently have less than 30 employees. That's about $4mm/year in employee costs. Let's assume that they spend another $6mm per year on hosting and bandwidth costs and other costs. So it's very possible that Craigslist's annual costs are around $10mm/year. Their value equation then is 10 x (100-10) = $900mm. That's almost a billion dollars in value for a company with only 30 employees.

The web can do that in more than one company. Last month, Spencer Ante reported that Digg's annual revenues were around $8.5mm. Everyone was saying how bad that was. And maybe it is, but I don't know. It wasn't the revenues that shocked me. It was the costs. Apparently Digg's costs for 2008 were about $14mm and they have over 70 employees and are planning on growing that number to 150 in 2009. Digg is entirely peer produced. It could take a Craigslist approach to its business and keep its headcount to around 30. Then it might be close to breakeven and could grow over time to a business with $30mm to $50mm in revenue and $10mm in costs and $20mm to $40mm in profits. Apparently Digg has been looking for an exit in the neighborhood of $300mm. They could get there with a lean cost structure possibly more easily than investing heavily in new stuff.

Facebook also comes to mind. Last winter, Kara Swisher reported that Facebook was planning on generating revenues of $300mm to $350mm in 2008 and that it would have profits of $50mm, meaning its costs would be $300mm in 2008. She also reported that Facebook would take its headcount to about 1000 by the end of 2008. As Chris said in his WSJ piece, Facebook has been widely derided for the low CPMs it generates (pennies in Chris' words). But instead of deriding the revenues that Facebook is generating, maybe we should be in awe of a $350mm revenue stream coming from a company that produces no content of its own. Why does Facebook need 1000 employees? Why does it need to spend $300mm per year? There may be good reasons. International expansion can be expensive and so is building out a large sales organization. But of course, none of that has to happen. Could Facebook instead cut is headcount back to 500ish and become incredibly profitable and still grow like a weed? I don't know that much about what is going on inside of Facebook and I am not trying to be critical of any one company. I am just trying to make a larger point.

Let's talk about the biggest and most valuable Internet company of them all, Google. Google has one incredibly amazing business – keyword advertising. It relies on its own search service and deals with other search services and content partners for the audience that drives the keyword business. If you stripped that business out of Google, you'd probably have a business that has gross revenues of $20bn, net revenues of $13bn, and operating profits of $8bn to $10bn. That business is worth the approximately $100bn of market value that Google has right now. Everything else is valued at zero becuase it has a lot of costs and no revenue. Could Google unlock a lot of value by giving up on everything else they are doing? Maybe not, but they probably wouldn't lose much value either. I am not suggesting they do that, by the way. But again, I just want to make a point.

The web can create incredibly high operating margin businesses. Craigslist has an operating margin of 90%. Google's keyword business has an operating margin north of 60% (based on net revenues) and possibly higher. Could Facebook and Digg copy those models and create a lot of value on revenue numbers that many think are pitifully small? I think so.

We have a bunch of companies in our portfolio that have done a lot with very little. For example, Tumblr has less than 10 employees, Disqus has 5, Twitter has around 20, Boxee has around 10. These companies are reaching large audiences and creating scale that can be monetized in many ways. We didn't tell these companies to stay small. They told us they could do a lot with a little. And watching them do just that has taught me a lot. Yes, they will all grow this year, most of our companies will. But if they continue to do a lot with a little, their business models will be built on operating margins that are very high and can create a lot of value without a lot of revenue.

I think that's an important part of the economics of the web that are left out of most discussions of Internet business models. Yes, we are turning analog dollars into digital pennies in many cases. But we are also doing the same thing on the cost side, maybe even more so. And I think that "operating leverage" is going to create a lot of value.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=5b0a002e-582c-4830-9d74-23304067f940)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=dacb1714-ff06-41a0-a227-efa8c6576df9)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=8d10e0a7-0460-4e39-9921-d6c28075de7f)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=49e7624c-1bf6-456f-8c7a-9366eb936630)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=c80c5d8e-49c8-4dff-aade-40edcff11526)